The 93rd Sutherland Highland Regiment of Foot 1800 - 1881

|

Formally gazetted into the Army in October 1800, the 93rd were dispatched from Fort George, via Aberdeen, to Guernsey. In February 1803, they were sent to quell a brief rebellion in Dublin. During these years they moved about Ireland, becoming quite popular with the Irish people because of their Gaelic language, high discipline and firm and steady conduct. The Regiment in its history would find itself many more times in Ireland. On one occasion a section was sitting in a tavern when a local bully came in challenging them to a fight. The smallest Highlander accepted, rose, lowered his head, ran and butted the bully in the stomach, flattening him. The rest drew their bayonets, cleared the tavern then quietly went back to their conversation and drink.

The 93rd sailed in July 1805 to help recapture Cape Colony from the Dutch. There the 93rd won their first battle honour. While landing 37 men were lost, still cheering madly as their boat capsized. In the ensuing battle the 93rd advanced in line, pipes playing, fired one volley and charged. The enemy broke and ran. After limited skirmishing over the next days Cape Town surrendered and the 93rd moved into Cape Castle, their home for the next eight years.

In an age of great illiteracy, especially in the army, the 93rd was amazing in that nearly every man could read and write. Almost every private had his own Bible - often having been given to him by his family. In Cape Town they built their own church, hired a Chaplain, taught school and gave to charities sending huge amounts home to help those in need. A remarkable, cheerful and united body of men given to music and Highland dancing. Such was their discipline and good conduct that while in garrison with other regiments the 93rd repeatedly was dismissed from Parade when corporal punishment commenced. Instead of having to see the example given by floggings, they instead became the example of discipline.

In August 1814 the 93rd sailed to Plymouth, England thinking of home. Instead on 17 September they embarked on three ships as part of a three-pronged offensive designed to chastise the United States and end the war dragging on there since 1812 when the U.S. declared war and invaded Canada. Napoleon had been sent into his first exile. Tens of thousands of veteran British soldiers were now free to be used in America. One prong of this strategy would attack through the Great Lakes region, the second front would smash into the eastern seaboard ultimately to burn the capital of Washington in retaliation for U.S. forces burning York (Toronto), Canada. The third - with the 93rd aboard - would attack through the Gulf of Mexico. Their final destination: New Orleans.

For this expedition the 93rd were ordered to wear tartan trousers (trews) and "hummel" bonnets in place of the kilt and feathered bonnet. No other Highland units were in this Division and as only Highland Regiments wore the kilt it is obvious then there were no kilted soldiers involved in the New Orleans campaign, contrary to what Hollywood movies (especially either version of "The Buccaneer") and some popular thought would like us to believe.

|

The 93rd landed on 23 December moving up the swamp. American militia attacked at night and a chaotic battle ensued. Elements of the 93rd helped turn the U.S. flank; by dawn superior discipline, training and the bayonet had prevailed over raw troops in the open. The Americans withdrew. Andrew Jackson would not dare to expose his rag tag army in such a way again. On 25 December the British commander arrived. Sir Edward Packenham, the "Hero of Salamanca" and the Duke of Wellington's brother in law. He was not pleased with the situation nor the terrain he found his army in. Jackson made his stand behind a make shift parapet along a canal 5 miles forward of New Orleans. The main British concern was the limited amount of room to maneuver before sweeping over this small obstacle: after all, in the wars with Napoleon fortifications ten times more massive and defended by professional soldiers had been breached and taken. Rain, sleet and cold assailed the men throughout the campaign. Packenham's advance on 28 December was halted 700 yards in front of Jackson's parapet and which withdrew not knowing the American left flank had been turned. Had the probe been turned into an outright attack, the outcome of the Battle of New Orleans might have been quite different indeed. As many as 30 guns were brought up by the British to try and reduce the American parapet which had been reinforced with mud and earth. (The cotton bales had proved useless and were mostly used as gun platforms.) The American artillery proved their worth many times over during this campaign, dislodging British artillery and eventually accounting for the horrendous casualty tally. An aborted assault was tried on 1 January, turning into an artillery duel.

Then came the calamatious assault of 8 January. Everything conceivable went wrong. The total result was for the army a disgrace; for the 93rd a tragedy. The Light Company helped to take a forward redoubt but without support were eventually driven out, captured or killed. The main body of the 93rd, some 960 men, moved up in column along the river road on the British left to reinforce where needed, originally to help the Light companies taking the advance US redoubt by the river. Then the British right faltered, US cannon fire from the west bank was continued and so the 93rd with pipes playing "Moneymusk" (the Regimental charge) was ordered to cross the field diagonally to assist the right flank. 100 yards from the parapet Regimental commander Colonel Dale ordered a halt - whether to begin forming an attack column or to ascertain the situation will never be known - he was killed immediately after. Their brigade commander, Gen. Keane, was also down, as was the commander of the British right flank, Gen. Gibbs. Many more 93rd officers fell. Packenham rode forward to rally his army and died not far from the 93rd, having previously called out, "Have a little patience 93rd and you shall have your revenge!" The Regiment had no further orders and so stood, "firm and immovable as a brick wall" as one American observer was to write. Other units broke and ran all round them. Most accounts of the battle state the British never even saw the Americans as the defenders would merely throw their firelocks up onto the parapet and fire without exposing even their faces. General Lambert, having taken command and seeing the 93rd standing their ground alone in the murderous artillery fire and haphazard musketry, sent orders for the Regiment to withdraw. Major Creagh, now in command, had first endeavored to advance but was at length compelled to turn back. So the 93rd came back in parade ground precision suffering between 300 to 500 casualties: three quarters of the Regiment's force and one fourth of total British casualties. The quiet stoicism of the 93rd was again displayed by the example of a 93rd man who lost an arm to the surgeon's knife. A friend lying next to him commented, "Jock, you'll never strike a man again with that arm." The man asked the surgeon for a last look at the arm and after contemplating the limb, hit his friend with it, saying, "You'll be the last!".

The New Orleans debacle must be blamed on a series of mistakes, bad luck, failure to execute certain elements of the battle plan and the generalship displayed at the time by Jackson. It should be noted that on the opposite (West) bank of the Mississippi River the British advance triumphed, driving the Americans from their line (they ran for two miles) and capturing artillery and colours. One of those cannons was engraved as having been captured from the British at Yorktown during the Revolution. This piece now stands in the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst.

The British remained in camp for ten days and by the 30th of January were finally embarked and gone. After leaving New Orleans the British captured Fort Bowyer outside Mobile. Two weeks later they learned of the peace treaty of Ghent, signed on 24 December but not ratified by Congress until two months later. Upon arrival back in Britain the 93rd was helped back to strength with men from a short-lived Second Battalion of the Regiment which had spent its existence as a garrison in Newfoundland. It was not enough nor soon enough to enable the Regiment to take part in Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo in June, though some officers of the 93rd were there with other units. It is interesting to note New Orleans was the only defeat ever suffered by the old 93rd - and it was the only time they wore trousers into battle.

For a more detailed look and some pop myth busting on the Battle of New Orleans,go here.

For a look at some shots from an A&E TV documentary film on the Battle which the 93rd SHRoFLHU worked on click here.

During the "long peace" following the end of Napoleon, the 93rd spent ten years in Britain and Ireland, eleven years in the West Indies from 1823 to 1834 (having the least number of deaths there of any regiment) being stationed variously at Barbados, Antigua, St. Christopher, Montserrat, St. Lucia and Dominica. Then three years at home. They came to Canada in 1838 to aid in quelling an insurrection there. From Nova Scotia the 93rd moved all about Canada. No.4 Company through the entire rebellion was attached to the 71st HLI in the Lower Provinces. The 93rd was present at the capture of the Windmill after which they were reunited at Toronto. The Regiment spent 10 years in Canada at various garrisons including Drummondsville, Montreal, and Quebec. One instance of note involved a Volunteer Regiment in garrison with the 93rd. These fellows continued over a long period to hurl abuse and insult at the stoically patient Highlanders until a gang of Volunteers actually beat up a 93rd Sergeant. At word of this the barracks emptied and a fisticuff battle ensued with the 93rd finally mauling and chasing the entire Volunteer battalion out of garrison and through the town. The commanders of both Regiments watched the proceedings helplessly, the 93rd Colonel at one point trying to intervene only to be lifted by a large 93rd Sergeant by one hand and gently set aside, whereupon the Sergeant saluted smartly and turned back to punching his adversaries. No charges were ever brought against anyone and there was no mention in any official army documents of the incident. It is safe to assume no one ever insulted the 93rd again, either.

In 1854 they were back in England when war broke out with Russia. By September they were in the Crimea. With the 42nd and 79th regiments they formed the Highland Brigade under Sir Colin Campbell, an old Napoleonic veteran and one of the few actually good generals in positions of command.

On 20 September the Brigade in full Highland uniform, with the Guards Brigade, waded the Alma River. Advancing in echelon, the British took the heights above while under constant heavy fire. The 93rd was engaged for the next months alternating in the siege of Sebastopol and serving garrison duty. On 25 October they were positioned to protect the main British supply base. A port called Balaklava.

Several thousand Russian cavalry had swept down and captured artillery batteries overlooking a small valley. They rode on with about five thousand continuing on the road to Balaklava, the others diverting to be cut down by the charge of the Heavy Brigade. The 93rd - about 500 including a few walking-wounded of other units - stood behind a ridge in the road to avoid the artillery now turned against them. As the Russian cavalry came nearer the 93rd moved forward and stood in line astride the road to the port and the British supplies. On either flank stood a battalion of their Turkish allies who fired an ineffectual volley at 800 yards, then broke and ran. (It may seem from a correspondence from a 93rd officer at the time that 50 casualties suffered by the Turks may have come from a volley purposely fired by a company of the 93rd into their fleeing allies!) Sir Colin Campbell rode down the line: "There is no retreat from here men, you must die where you stand." A chorus was taken up by the 93rd in answer, "Aye Sir Colin, and needs be we'll do that." Campbell did not form the regiment into the usual square formation to withstand cavalry but rather left them in line, later commenting, "I knew the 93rd, and knew there was no need (to form square)." They fired a volley at 500 yards from their rifled muskets and another at 250 yards. They commenced fire by files. The cavalry split in half and veered to the left and right wheeling back. The Grenadier Company wheeled right to fire once more into the horsemen to refuse the flank and insuring the enemy's retreat. On a hill above, London Times correspondent W.H. Russell watched and wrote of nothing standing between the cavalry and the supply base but "the thin red streak tipped with steel". This news report gained the Regiment immortality and gave them their nickname. The phrase was popularly condensed to become "THE THIN RED LINE".

The 93rd suffered as other regiments from cold and disease through the rest of the war. Finally they returned home in June 1856 to great acclaim. Only a year later they were diverted from their destination of China to land in Calcutta and be reunited with Sir Colin to help quell the Indian Mutiny.

Having seen the grisly, slaughterhouse remains of the men, women and children prisoners murdered out of hand at Cawnpore by rebellious Sepoy regiments' mutineers, the 93rd, with other British and loyal Indian units fought with a vengeance up to Lucknow where the beleaguered Residency still held out. On 11 November 1857 the 93rd faced the two great fortified enclosures of the Sikander Baugh and behind it the Shah Najif. The 93rd swept forward to the pipes playing the "Haughs of Cromdell". Nine officers and men got through a hole in the wall and, fighting hand to hand held the way open for the rest, eventually forcing the gate open. Fierce fighting continued and as evening fell the enclosure was cleared. Two thousand mutineers lay dead inside, most of them killed by the bayonet. Sir Colin called on the 93rd once more and sword in hand led them against the Shah Najif. After a terrific cannonade against the walls with little effect and hostile fire beating down, a 93rd Sergeant literally found a back door in. The Regiment rushed round and inside to see the last of the mutineers scurrying out yet another back way. At dawn the Highlanders uncased their Colours on top of a tower inside so those in the Residency knew relief was at hand. Drummer boy Ross who helped in this feat played "Yankee Doodle" on his bugle "so my American cousins (Canadian relatives) would know I was here!". The harried defenders of the Residency were brought out safely and the 93rd had won six Victoria Crosses.

This was not the end as the relief force now had to escort the relieved to safety and then turn its attention on the rebels occupying Cawnpore once more. From 29 November to 6 December the 93rd was engaged in helping drive out and disperse the rebels. On 1 March 1858 the Regiment with the rest of the army arrived back at Lucknow to finish the job. Lucknow was now the center of rebel power. Over the next few days the British were involved in enclosing the enemy and retaking that which had been so dearly won previously. On the 11th the 93rd assaulted the strongly garrisoned and fortified Begum Kothi, practically repeating their performances earlier. Fierce hand to hand combat was again carried through the fort. Adjutant Wm. McBean was awarded the V.C. for encountering eleven of the enemy in succession and cutting them down with his sword. (McBean was one of those rare fellows: enlisted as a private at age 16, held every rank in the army, never leaving the Regiment, eventually commanded the 93rd and died an honourary Major-General.)

Artillery fire finally formed a small hole in the wall. Pipe Major John McLeod was the first to enter the breach. No sooner was he in than he began and continued through the entire fight to encourage the men with his bagpipe music. By the 21st the fighting in the city was over. There was still long, hard campaigning over the next months against scattered rebels before the 93rd finished with the suppression of the Mutiny. Then it was long years of garrison duty and border fighting in India, including the Umbeyllah Campaign. It would not be until March 1870, twelve and a half years later, that the Regiment would stand once more in Scotland.

The 93rd spent 9 happy years at home in Britain. In 1879 they were sent for 2 years to Gibraltar. In 1881 came a reorganization of the British army and the 93rd was amalgamated with the 91st Argyllshire Regiment, becoming the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders (Second Battalion). Over the long years since, the Regiment carried on with duty and dignity in peace and war. The worst "battle" was with the War Office in the 1960's to remain in existence after the famous Aden affair with Lt. Col. "Mad Mitch" Colin Mitchell in command. Public outcry and a petition with one million signatures helped keep the Regiment alive. Through war, disease, capture and further amalgamation with the First Battalion, the 93rd has lived on. Today "The Thin Red Line" still stands firm in our ever changing world.

A&S Highlanders in Iraq.

The Colonel-in-Chief:

If ever in Scotland, visit the

To get a History of the 93rd with names and dates in a nutshell go to a Concise History of the 93rd

Sources used for this article:

"Battle of New Orleans" by Col. Chs. H. Waterhouse. In many respects a good depiction of the attack on the parapet after the British capture of the advance redoubt next to the river bank. However, errors exist: This scene makes it appear the handful of US Marines actually present single-handedly engaged and stopped the enemy. (As this was painted by a Marine, it's understandable.) The US counterattack was also made up primarily of men from the 7th US Infantry and Beal's Rifles (a local militia). We also do not see any men from the Light Companies of the British 7th and 43rd Regiments who were involved in this attack, nor do we see any of the advance redoubt which had just been overrun and captured. For once the 93rd Highlanders are shown correctly in trousers. There is speculation some, due to shortage of tartan issue, were in grey trousers. The red stripe of the officer's pants is debatable. He should also be wearing wing style epaulettes for a flank company and carrying a sabre, not a baskethilt, and sword baldric with slings. As it was the Light Company involved, the men's shoulder wings are correct, however, the touries (pompoms) on the top of the bonnets should be green for Light Coy. Also debatable is the presence of US troops on top of the parapet - as all eyewitness accounts state the US troops never showed their faces above the parapet and at this position of the battlefield - inside the redoubt and behind the parapet - an uneasy stalemate occured with both forces keeping their heads down for fear of being shot. Of course, the musket swinging "Davy Crockett" style stance of the Marine at top left is plain silly.

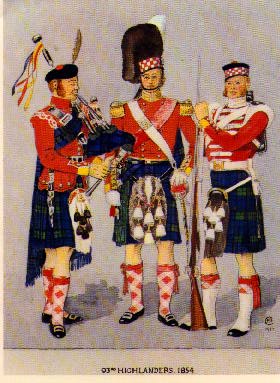

93rd uniforms during the Crimean War: left to right, Piper, Officer, Private, all of a battalion company.

"The Relief of Lucknow" by Ernest Ibbetson. An excellent view of the era. The white quilting around the bonnet bottoms are sun shades. The brown dust jackets actually cover the red wool doublets - rather than replacing the hot wool! The soldier to our left of the officer must be a sergeant as he is wearing a badger sporran, though no stripes are discernible on his sleeves.

Capt. W.G.D. Stewart

C/Sgt. J. Munro

Sgt. J. Paton

L/Cpl. J. Dunley

Private P. Grant

Private D. MacKay

Lt. WM. McBean

Memorial to the Fallen of the 93rd during the Indian Mutiny, in St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh.

"Outnumbered British soldiers killed 35 Iraqi attackers in the Army's first bayonet charge since the Falklands War 22 years ago. The fearless Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders stormed rebel positions after being ambushed and pinned down.

Despite being outnumbered five to one, they suffered only three minor wounds in the hand-to-hand fighting near the city of Amara. The battle erupted after Land Rovers carrying 20 Argylls came under attack on a highway.After radioing for back-up, they fixed bayonets and charged at 100 rebels using tactics learned in drills. When the fighting ended bodies lay all over the highway � and more were floating in a nearby river. Nine rebels were captured.

An Army spokesman said: "This was an intense engagement." The last bayonet charge was by the Scots Guards and the Paras against Argentinian positions. "

The Colonel of the Regiment:

Regimental Headquarters & Regimental Museum:

The Regular Army:

The Territorial Army:

The Army Cadet Force:

Alliances:

Affiliations:

Regimental Association: Headquarters: Stirling Castle

Branches:

Freedom Burghs:

Opening times:

Easter - September:

Monday to Saturday 10am to 5.45pm

Sunday 11am to 4.45pm

October - Easter:

10am - 4.15pm

Telephone: 01786 476165

One may also view 93rd relics at Dunrobin Castle in Sutherland and at the United Services Museum in Edinburgh Castle.

"Historical Records of the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders", compiled and edited by Roderick Hamilton Burgoyne, late 93rd Highlanders. London, 1883.

"An Reisimeid Chataich, The 93rd Sutherland Highlanders", by Brig. Gen. A.E.J. Cavendish, CMG. 1928. Published Privately.

"History of the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders...1800-1895", by Lt. Col. Percy Groves, R.G.A. W & AK Johnston, Edinburgh & London, 1895.

"Records of Service and Campaigning In Many Lands", by Surgeon-General Munro, MD, CB., late of 93rd Highlanders. London. 1887.

"Reminiscences of Military Service with the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders", by Surgeon-General Munro, MD, CB., formerly surgeon of the regiment. London. 1883.

"Reminiscences of the Great Mutiny 1857-59", by Wm. Forbes-Mitchell, late sergeant 93rd Highlanders. London. 1895.

"Recollections of A Highland Subaltern", by Lt. Col. W. Gordon-Alexander, late 93rd Highlanders. London. 1898.

"Fighting Highlanders! The History of The Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders", by Major P.J.R. Mileham. London. 1993.

"Famous Regiments, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders", by Douglas Sutherland, M.C. London. 1969.

"The Scottish Regiments 1633-1987", by Maj. P.J.R. Mileham. 1988.

"The Scottish Soldier", by Stephen Wood. Manchester. 1987.

"Soldiers of Scotland", by Lt. Col. John Baynes Bt, M.Sc. 1988.

"The Highland Brigade in the Crimea", founded on letters written during the years 1854, 1855 & 1856, by Lt. Col. Anthony Sterling, "a staff officer who was there".

"A History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army", by Major R.M. Barnes. London. 1950.

"Scottish Military Uniforms", by Robert Wilkinson-Latham. Hippocrene Books, 1975.

"Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders", by Wm. McElwee and Michael Roffe. Osprey. 1972.

"The Naval War of 1812" by Theodore Roosevelt. NY, 1889.

"Blaze of Glory - the Fight for New Orleans 1814-1815" by Samuel Carter III, St. Martin's Press, NY.

The Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812", by Benson Lossing, NY 1869, reprint 1976.

"The British at the Gates-The New Orleans Campaign in The War of 1812" by Robin Reilly. Putnam, NY 1974.

"Amateurs to Arms", by Col. JR Elting.1991.

"With Musket, Cannon and Sword - Battle Tactics of Napoleon and His Enemies" by Brent Nosworthy.

"The Armies of Wellington" by Philip J. Haythornthwaite. 1994.

"Weapons and Equipments of the Napoleonic Wars", by Philip J. Haythornthwaite. London, 1996.

"British Infantry Of The Napoleonic Wars", by Philip J. Haythornthwaite. London, 1987.

"Life In Wellington's Army", by Antony Brett-James. London, 1994 edition.

"The Campaigns of the British Army at Washington and New Orleans, 1814-1815" by Rev. G. R. Gleig. London 1827.

"A Subaltern in America, Comprising His Narrative of the British Army at Baltimore, Washington, etc..", by Rev. G. R. Gleig. Philadelphia, 1833.

"British Sieges Of The Peninsular War", by Frederick Myatt. Spellmount, UK, 1987.

"The Dawn of Modern Warfare - History of the Art of War, Vol. IV", by Hans Delbr�ck (1848-1929). Translated by Walter J. Renfroe, Jr. Univ. of Nebraska, 1990.

"Biographical Sketches of the Veterans of the Battle of New Orleans 1814-1815" by Ronald R. Morazan. Legacy Publishing, 1979.

"Frederick The Great on the Art of War", edited & translated by Jay Luvaas. NY, 1966.

"Military Marching - A Pictorial History", by James Cramer. Forward by Lt. Gen. Sir Napier Crookenden, KCB, DSO, OBE, DL. Spellmount, 1992.

"The Face of Battle", by John Keegan. NY, 1976.

"The Mask of Command", by John Keegan. 1987.

"Firepower - Weapons Effectiveness On The Battlefield, 1630-1850", by Maj. Gen. B.P. Hughes, CB, CBE. NY, 1997.

"The FootSoldier", by Martin Windrow & Richard Hook. Oxford Univ. Press, 1982.

"Forward into Battle-Fighting Tactics from Waterloo to the Near Future" by Paddy Griffith (16 years senior lecturer in War Studies at Sandhurst). Presidio Press, Novato, CA. 1990.

"The Elements of the Science of War; Theory and Practice" by William Muller KGL 1811. (classic example of Pakenham's tactics being "by the book".)

"The War of 1812 - A Forgotten Conflict" by Donald R. Hickey. Univ. of Illinois Press. 1989.

"New Orleans 1815 - Andrew Jackson Crushes the British" by Timothy Pickles. Osprey, 1993.

"The American War 1812-1814", by Philip Katcher, Osprey, 1990.

"Twenty-Five Years in the Rifle Brigade" by W. Surtees, 1833. Reprint by Greenhill Books.

"A Full and Correct Account of The Military Occurrences of the Late War Between Great Britain and the United States of America", by Wm. James, 1818.

"The Battle of New Orleans - A British View", the Journal of Major C.R. Forrest, Asst. Quarter Master General, New Orleans Campaign. Intro and annotations by Hugh F. Rankin. The Hauser Press, New Orleans, 1961.

"Rough Notes of Seven Campaigns in Portugal, Spain, France and America, 1809-1815", by John Spencer Cooper, late Sergeant, 7th Royal Fusiliers. Reprint of 1869 publication by Spellmount, 1996.

"The Siege of New Orleans", by Charles B. Brooks, Univ. of Washington Press, 1961.

"Various Anecdotes and Events of my Life --The Autobiography of Lt. Gen. Sir Harry Smith, covering the period 1787 to 1860", by Sir Harry Smith. First published in 2 volumes, edited by G.C. Moore, London, 1901.

"The Historical Memoir of The War in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814-15, with an Atlas", by Ars�ne LaCarri�re Latour, Major, principal engineer 7th Military District US Army, originally published 1816. The Historic New Orleans Collection and University of Florida Press. reprint 1999 - expanded edition edited by Gene A. Smith.

"The Amphibious Campaign for West Florida and Louisiana, 1814-1815", by Wilburt Brown (Maj. Gen. USMC, retired), University of Alabama, 1969.

"The Dawn's Early Light", by Walter Lord, NY 1972.

"The War of 1812 - Land Operations", by George F.G. Stanley. MacMillan & national Museum of Canada, 1983.

"When They Burned The White House", by Andrew Tully. NY, 1961.

"The Baratarians and the Battle of New Orleans", by Jane Lucas de Grummond. Baton Rouge, 1961.